Rosamund Bentley

In 1779, three years after the Declaration of Independence was signed, Rosamund Bentley undertook her own fight to secure her freedom by pursuing legal action against her enslaver, Anthony Addison.

Bentley had been born into slavery under Maryland’s 1664 act, which assigned children the same legal status as their fathers. The law had been passed to discourage interracial marriages.

Bentley’s great-grandmother was a White indentured servant named Mary Davis who had married Domingo, a man legally classified as an enslaved African. Using eyewitness and other sworn testimony, Bentley claimed that her great-grandfather's racial identity had been erroneously categorized, and that he was of American Indian rather than African origin. She argued that the law instituted in 1664, which condemned children born following its enactment to lifelong enslavement, did not apply to her mother, grandmother, or her. She successfully convinced the Maryland court and won her case in 1779. However, the official documentation affirming her freedom and that of her daughters was delayed for five years.

Watercolor illustration of an overseer and two enslaved women, Virginia, 1798.

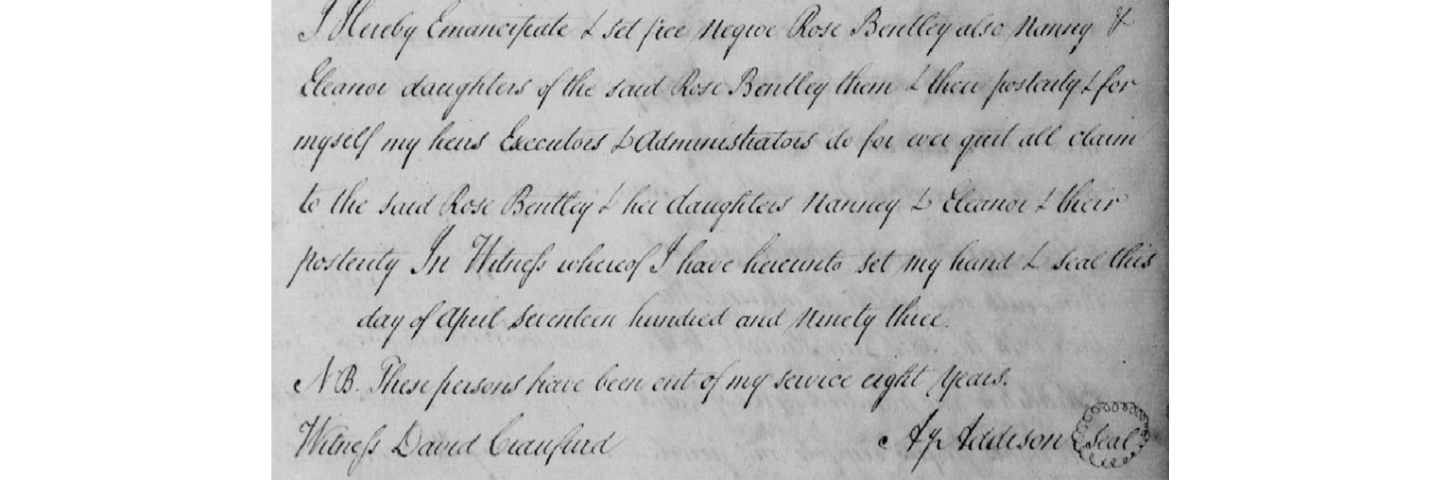

Click the + to view the manumission document of Rosamund Bentley and her children.

I Hereby Emancipate & set free negroe Rose Bentley also Nancy & Eleanor daughters of said Rose Bentley them & their posterity & for myself my heirs Executors & Administrators do for ever quit all claim to the said Rose Bentley & her daughters Nancy & Eleanor & their posterity In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand & seal this day of April Seventeen hundred and Ninety three.

[illegible] These persons have been out of my service eight years.

Witness David [illegible] A. Addison

– Manumission of Rosamund, Nancy, and Eleanor in 1793