Human Consequences: Radiation and Fallout

When nuclear weapons are detonated in the atmosphere, they release dangerous by-products, which are carried through the air in fallout. Radiation in fallout causes short- and long-term damage to humans and the environment.

When atomic bombs were dropped on Japan in 1945, radiation was known to be harmful to humans, but the full extent of this danger was unclear. Similarly, with testing in the Marshall Islands (in the Pacific Ocean) and other locations, scientists were uncertain how severe the effects would be. Some used these tests to study how people were affected by radiation. The effects of nuclear weapons on humans are now well documented.

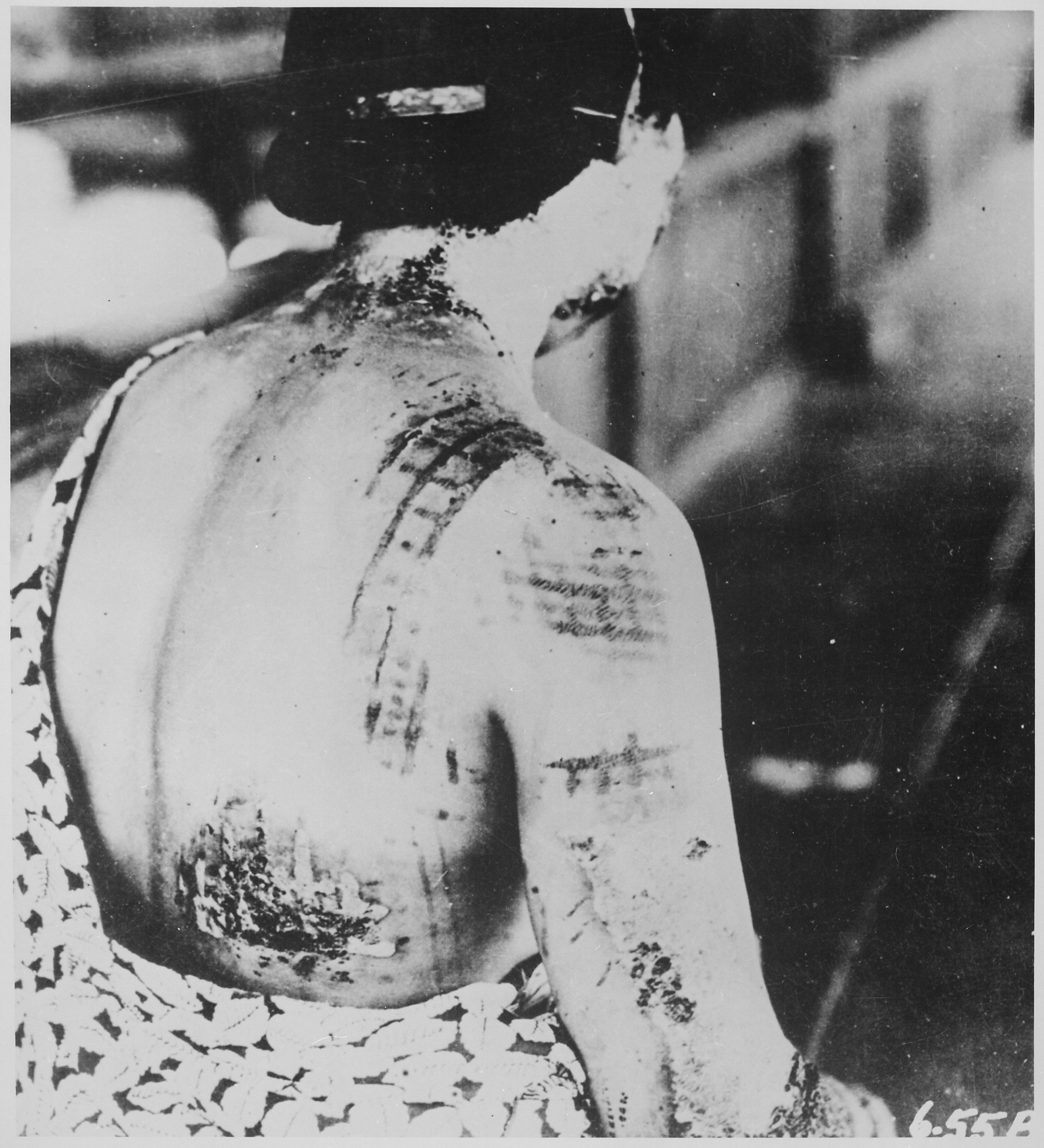

- Combined casualty estimates for Hiroshima and Nagasaki range from 110,000 to 210,000, with most victims perishing at the time of the bombings or soon after. Radiation had an immediate, sometimes fatal, impact and also delayed consequences that resulted in disease or death years later. Further, cultural stigma and discrimination (often over mistaken ideas about radiation) harmed Japanese atomic survivors for years after the war had ended.

- After U.S. nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands, residents returned to their homes while radiation levels were still high. Information provided to the Marshallese (people from the Marshall Islands) concerning the risks was scarce or deliberately misleading. Some U.S. scientists said that it would be valuable to study radiation’s effects on the Marshallese because the testing area was “by far the most contaminated place in the world.” Studies found that the nuclear tests resulted in increased birth defects and elevated cancer rates.

- The United States, the United Kingdom, and France all tested in areas outside of their home borders, causing severe damage and health issues for those living near the test sites and up to thousands of miles away. Dangerous by-products from nuclear explosions in the atmosphere spread worldwide, resulting in global health consequences. Levels of one dangerous by-product, strontium 90, increased a hundredfold between the 1940s and early 1960s.

Hiroshima radiation victim, 1945.

–A U.S. government scientist referencing the testing contamination of the Marshall Islands and the use of the Marshallese as test subjects, 1956

Take Notes

When developing a new weapon, what are the ethics of testing on civilian populations? Write three or four sentences explaining what you think is ethically correct when considering the possible value of a new weapon versus the risks to people who might experience harm as a result of use or testing.