The Story of Ashfall

In 1971, Mike discovered an exciting site on Melvin Colson's farm, where erosion revealed layers of sandstone and volcanic ash. His exploration led him to a ravine that turned out to be filled with fossils. With experience, he understood that areas with exposed rocks are great for finding fossils. Eighteen years later, he noticed a color change in the rocks and found a baby rhino skull embedded in the bank. This discovery sparked a significant excavation in 1978, supported by the National Geographic Society. Over two summers, Mike and a team worked diligently to unearth complete skeletons of rhinos, horses, camels, and more. They faced challenges like volcanic ash but made notable discoveries, including an adult rhino. This major find helped scientists plan for future digs in the area.

In this video you will learn:

- Why this site was chosen as an area possibly rich in fossils.

- About the first skeletons that were unearthed.

- The conclusions paleontologists have made about the animals.

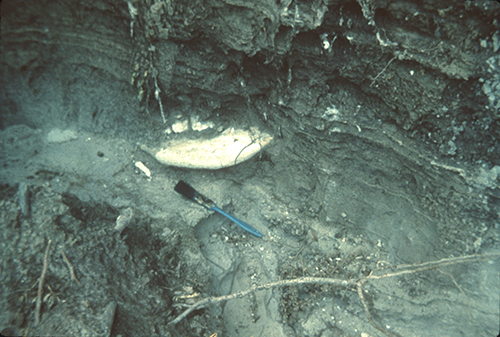

The baby rhino jawbone found by UNSM Paleontologist Mike Voorhies, setting off the discovery of many more skeletons and what is now Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park.

Mike Voorhies, UNSM Paleontologist Emeritas and Greg Brown discuss the findings, the history and importance of the Ashfall Fossil Beds to students and fellow scientists.

| Keyboard Shortcut | Action |

|---|---|

| Space | Pause/Play video playback |

| Enter | Pause/Play video playback |

| m | Mute/Unmute video volume |

| Up and Down arrows | Increase and decrease volume by 10% |

| Right and Left arrows | Seek forward or backward by 5 seconds |

| 0-9 | Fast seek to x% of the video. |

| f | Enter or exit fullscreen. (Note: To exit fullscreen in flash press the Esc key. |

| c | Press c to toggle captions on or off |

NARRATOR: In 1971 Mike's curiosity was drawn to an eighty foot cliff on the farm of Melvin Colson. Erosion had exposed a huge layer of sandstone and volcanic ash.

MIKE VOORHIES: And any paleontologist worth his salt would immediately, once he saw that thing, have to climb up it and take a look at it, and see what's there.

NARRATOR: Mike's curiosity paid off beyond his wildest dreams. He continued to explore the area, ending up in this ravine.

It was the beginning of a world class fossil bonanza.

MIKE VOORHIES: Well, gentlemen, this is sort of like coming home after eighteen years of being away. This is the ravine where the ash bed was exposed the first time that I saw it. People are always asking, "How do you know where to dig," and experienced bone

hunters like you, Greg, know that you really don't know where to dig. But a clue is always. you've got a rock exposure like this, so your chances of finding fossils are a lot better in a place like this.

And eighteen years ago I noticed a change in the color of the rocks up here, and traced the ash bed around. And it got sort of narrow up at the top, you kind of wiggle through, just about room enough for your hips. And there was a baby rhino skull sticking out of the side of the bank up there, like the only intact skull and jaws of a rhino that I'd seen in all my years looking for fossils in Antelope County.

NARRATOR: But that wasn't all Mike found. Five more rhinos emerged from the dust. It was time for a major excavation. That began in 1978 sponsored by the National Geographic Society. Mike and museum preparators from the Nebraska State Museum cleared an area the size of a basketball court. Like detectives at a crime scene, the crew excavated the sight from sun up to sun down during two consecutive summers.

What emerged was astounding. It was a unique world class discovery. Complete skeletons of rhinos, horses, and camels,and partial remains of birds, turtles, deer, and rodents were unearthed from the ten million year old dust. Never before had such complete remains been found, nor so many.

MIKE VOORHIES: My brand of paleontology is fairly low-tech in the sense that we use pretty much the same methods of excavation that were used maybe

a hundred years ago. It's not as though we intend to use primitive methods. It's just that there's really no substitute for excavation with small tools,

fine soft brushes, so that we don't disturb any of the delicate fossils.

(SCRAPING)

MIKE VOORHIES: Ah, That's the sound you want to hear, metal on bone. In some ways fossil collecting is like farming. You have to have a little bit of patience. You can't expect the crop to just pop up out of the ground and be ready for you.

NARRATOR: Like farmers the scientists have little control over weather conditions while they're working, and consequently, must continue even when the air is full of volcanic ash.

MIKE VOORHIES: Ordinarily you get even a ten or fifteen-mile-per-hour wind, this place looks like a blizzard out here because that ash blows in the air. Can't keep them clean off for more than a couple seconds.

NARRATOR: By the end of the summer they complete a giant grid, an elaborate trench system that allows Mike and his crew to plot out future fossil finds. Along the way they've uncovered an adult rhino, an encouraging peek at what's to come.

MIKE VOORHIES: This critter with the scientific name Teleoceras has always been a mystery, because its teeth and its body don't seem to go together. Normally you think of

an animal that eats grass should live out on the open plains and it ought to have long, graceful legs. But here's, it almost looks like nature made a mistake and gave it this

barrel-shaped body and short, stubby, little legs. And teeth that were adapted for eating grass.

But when you look at the hippopotamus, then the mystery is solved, because there's a grass-eating animal with short legs. Here's the tooth in the upper jaw that grinds against the lower tusk. This is the first incisor. Had a fairly wicked tip on the tusk. So probably, like the Asian rhinos of today, they did a lot of fighting with their front teeth.

(DIGGING)

MIKE VOORHIES: Oh boy, that is, that is pretty.

GREG BROWN: You know it's, just looking at this head though, it's kind of interesting 'cause it's laying on its left side. The nose is here, the back of the head here. The eye would be here. This would be the cheek bone. Here's the articular surface of the lower jaw. Lower jaw comes around this way. You can see a few teeth here. And right up in front in the lower jaw is a very, very small front tooth, which shows it to be a female and fairly young.

MIKE VOORHIES: That is a beauty.

GREG BROWN: It's a very eerie feeling to see rhinos just as they died, exhibiting that much, almost that much life in death. You can almost feel the agony they were going through. Some cases almost look like the baby rhinos were trying to nurse even after their mother had died. So it really brings up some vivid pictures for your imagination.