What is radical resistance?

David Walker was born in the late 1790s in North Carolina to an enslaved Black man and a free Black woman. In most slave states, children inherited the legal status of their mother. As a result, Walker was legally free. However, he was not immune to the suffering of over 1.1 million Black people who remained enslaved in the South. After traveling extensively, Walker settled in Boston, opened a clothing store, and joined an established community of Black northern abolitionists. Walker joined the Massachusetts General Colored Association, believed to be the first Black abolitionist organization, and quickly rose to prominence.

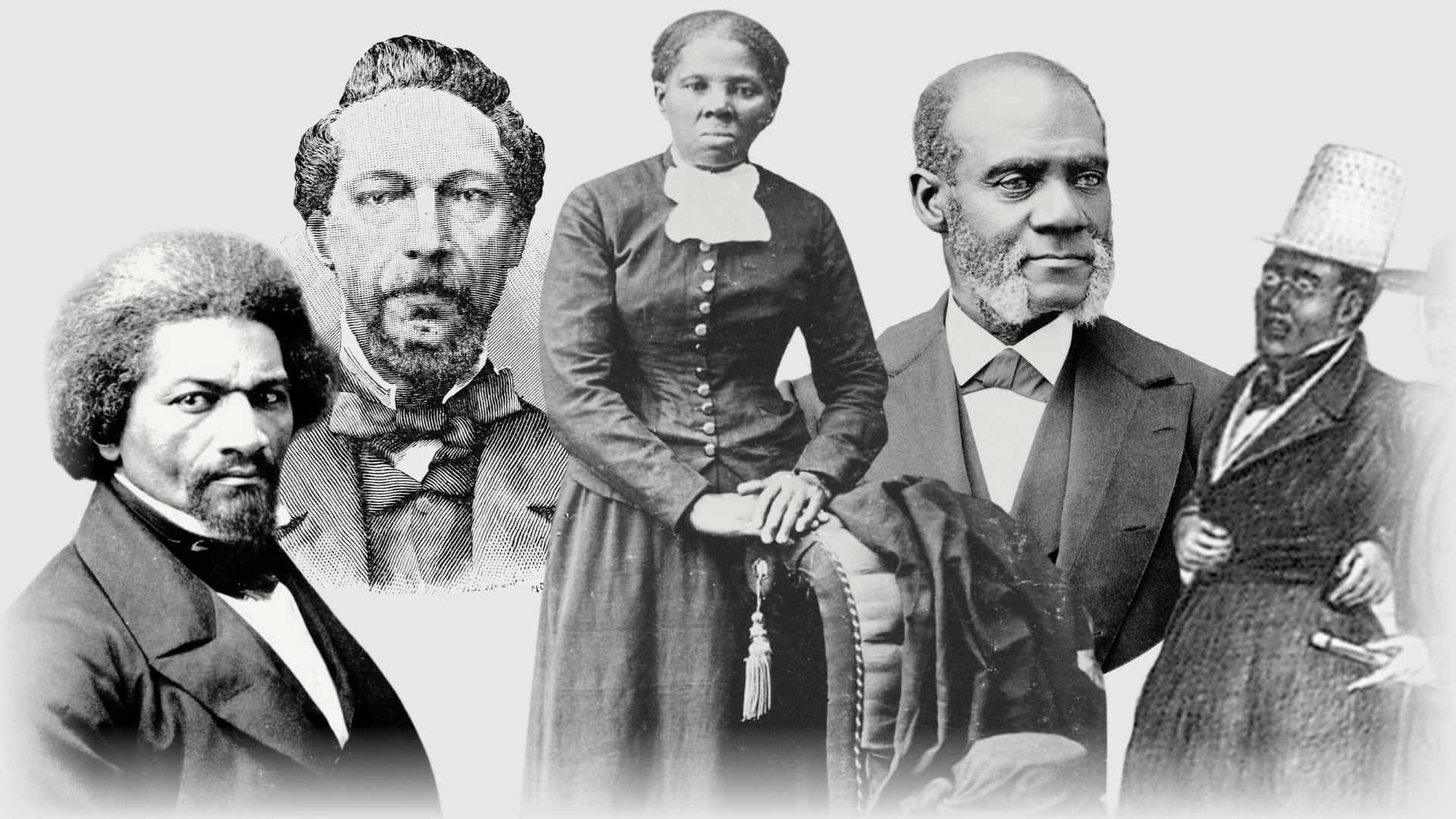

From left to right: Frederick Douglass, Phillip Bell, Harriet Tubman, Henry Highland Garnet, and David Ruggles.

Although Black and White abolitionists worked together, their relationship was complex. In many cases, White abolitionists refused to see Black abolitionists as their equals. There were also disagreements over the most effective strategy for abolishing slavery. Many White abolitionists favored gradual abolition, a strategy used by many northern states where laws specified dates or ages at which enslaved people would be emancipated. Another strategy was moral suasion, a strategy focused on convincing White people that slavery was immoral and inconsistent with the nation’s democratic principles. Walker was a proponent of radical resistance, another strategy. Supporters of radical resistance advocated the immediate and direct overthrow of slavery by any means, including revolution, and believed that the Declaration of Independence validated their stance against slavery. For them, direct resistance was the only way that the expansion of slavery could be eliminated.