Freedom in Action

Policy makers in the U.S. were actively involved in establishing the United Nations, which came into being shortly after the end of World War II in 1945. Its stated purpose was to bring peace to all nations of the world. The United States was one of 51 founding nations, and the UN headquarters were built in New York City.

The Philippines, an overseas territory of the United States since 1898, was attacked and occupied by Japan during World War II. Filipino underground and guerrilla forces battled against Japanese occupation forces throughout the war, and were rejoined by Allied troops in 1944. In 1946, the United States followed through on the plan put into place 10 years earlier with the Filipino administration, formally ending the colonial relationship. While the Philippines gained sovereignty, the U.S. retained its claim to dozens of military bases in the country and still played a major economic role.

During and after WWII, an organization called the Jewish Agency brought millions of Jewish immigrants (including hundreds of thousands of Holocaust survivors) to Palestine. On May 14, 1948, Jewish Agency head David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the establishment of the State of Israel. Many prominent members of President Harry S. Truman’s administration argued against recognizing Israel, placing the U.S. in the middle of the conflict between the Jewish people seeking to establish their own nation and the Palestinian Arabs who did not want to lose their home territory. Truman’s advisor, Clark Clifford, made the following argument to the president:

“It is important for the long-range security of our country...that a nation committed to the democratic system be established [in the Middle East].... The new Jewish state can be such a place. We should strengthen it in its infancy by prompt recognition.”

Truman officially recognized the state of Israel that same day.

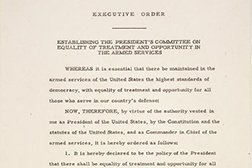

Following up on such wartime efforts as the Double V Campaign, led by African Americans to encourage support for the war abroad and for the elimination of segregation at home, President Truman signed an executive order on July 26, 1948, establishing the President's Committee on Equality of Treatment and Opportunity in the Armed Services, setting in motion the integration of the military.

Take Notes

In what ways do these actions reflect a commitment to “freedom” as it came to be understood in the 1940s?